Halfway through our Green River, Labyrinth Canyon final section, we stopped at Trin Alcove for a layover day to work on our final papers and take in our surroundings. Midday we were given some “silent solo” time, a specifically non-academic chunk of time to hike up one of the three side canyons, find a spot to sit, and simply be.

After turning around at a poison ivy fenced alcove, I walked to the opposing wall of the canyon. Hidden in the shade, a puddle of life existed. With red rock dust caked into my legs and warmth soaked into my shoulders, I submerged myself into the small pool. Cold sand formed around my legs and I noticed a group of minnows hiding behind a rock. Their yellow and black bodies graced through the settling water as they swam up to me, unsure of this foreign object. Precautionarily dancing around my feet one grazed my skin, surprising my nerves and causing a sudden jerk. Realizing the fear I had caused when they fleeted back to their rock, I tried to relax into the system. Emerging once again, one of the minnows swam up to a clawed mini-crustacean that I had not seen before. I felt as if I were watching them converse. As suddenly as I had seen it, the crustacean flew backwards in the water, jumping away from my movement.

Quickly thereafter, I noticed the sunscreen from my arms seeping into the water. Worried for the effect it would have in this ecosystem, I hopped out and observed from the shore. With the afternoon sun on my back, I embraced the wonder. The awe of this ecosystem and all that happens within it. The humility of its more than human existence and the imposition that I had caused. I wondered about the future of this pool. In the coming months would a flash flood connect them to the greater Green River? Or was it their path to end their lives with the beginning of the dry summer heat? What would the effects be of the chemicals I unintentionally spewed or the sand that I stirred up?

While questions of their future, species names and habitat zones circled in my head, I was also taken with the simple beauty of this singular ecosystem. The “sudden surprise of the soul,” as Descartes worded, that had taken control of this moment. Dorsal fins reflected sun while water skeeters’ shadows formed dots on the sand below; beautiful, whole, interdependent, resilient. This system existed without me, but how lucky I was to have been able to see it.

Further downstream in Labyrinth Canyon, the article “Introduction to Bioregionalism,” by David Barnhill, synthesized many of the place-based experiences and emotions that I have had. “Bioregionalism is an ecological movement centering on one’s local geographic area – one’s bioregion. On the personal level it focuses on cultivating an intimate personal connection to the local bioregion. On the community level, it seeks to develop social, political and economic structures in harmony with the specific land of the area” (Barnhill). It encompasses ideas of decentralized politics, economy, agriculture and power. The idea fosters localization and intention towards interdependence. However, one thing this article and other readings on bioregionalism have failed to acknowledge is the Indigenous ecological knowledge and spirituality that bioregionalism “synthesizes.” In quoting Peter Berg, a bioregion activist, Barnhill writes that “a bioregion refers to both the geographical terrain and a terrain of consciousness – to a place and the ideas that have developed about how to live in that place.” While this consciousness includes ecology, geography and a sense of place, I would argue that a “sense of wonder” should be included in defining bioregionalism.

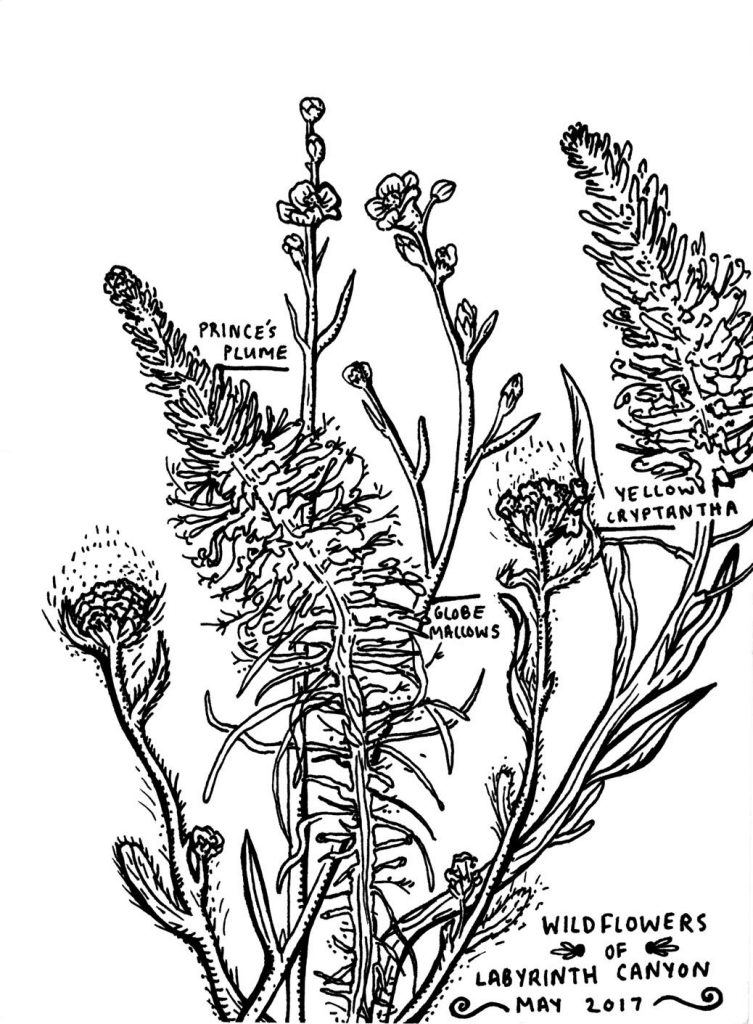

During the course of WRFI, I have come to learn some of the bioregional knowledge that the Colorado Plateau has to share. With time I have come to learn the orientation of mountain ranges and water arteries, the geologic layers and environments of deposition that we have hiked through, which plants are invasive, how to identify a swift verses a swallow, tricks to reading canyon topography, and knowledge that goes beyond identification and classification. What I have learned about natural history and bioregionalism here will now be a part of my perspective in any bioregion and landscape that I travel through.

Beyond this, I have an awakened sense of wonder! Kathleen Dean Moore, in “Ethics and the Environment- The Truth of Barnacles: Rachel Carson and the Moral Significance of Wonder,” poetically states how “wonder is the open eyes, the sympathetic imagination and respectfully listening ears, seeking out the story told by nature’s rough bark and flitting wrens, and by that listening, entering into a moral relationship with the natural world.” I shall continue this sentiment and pursue the idea of wonder as the morality of interconnectedness.

In describing Rachel Carson’s piece “The Edge of the Sea,” Moore explains how “Carson shows us that a sense of wonder is not just a way of feeling or a way of seeing, it is a way of being in the world. To contemplate, and thereby acknowledge the meaningfulness and significance of the other, opens the door to a moral relationship.” Imagine the possibilities of cultivating a wonder relationship with every bioregion that is inhabited by humans, the awareness, humility, intent and sense of community that it would bring to many aspects of life. But rather then imagine, this way of being can be lived.

“Some philosophers and scientists would have us believe that they are separate worlds, the “is” and the “ought.” But I believe the worlds come together in a sense of wonder. The same impulse that says, this is wonderful, is the impulse that says, this must continue. A sense of wonder that allows us to see life as a beautiful mystery forces us to see life as something to which we owe respect and care. If this is the way the world is: extraordinary, surprising, beautiful, singular, mysterious and meaningful, then this is how I ought to act in that world: with respect and celebration, with care, and with full acceptance of the responsibilities that come with my role as a human being privileged to be a part of that community of living things. Wonder is the missing premise that can transform “what is” into a moral conviction about how one ought to act in that world.” – Kathleen Dean Moore

We must “savor the rush of remembered delight” (Ibid), “live openly, deeply and gratefully” (Moore), live with respect, relationship and reciprocity towards all life, have an inclusion of interdependence throughout all movements, and cultivate, embrace and celebrate a sense of wonder so deep it goes beyond a childlike sense of curiosity to include a humanlike sense of true being.